Green but Not Clean: The Hidden Cost of Electric Cars

Author: Josephine Davina Adhi

Electric cars are widely recognized as one of the greatest innovations in the effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. They represent the vision of a cleaner future, where vehicles move silently through cities without producing harmful smoke. Governments and companies have invested billions of dollars to accelerate the transition to electric transportation, hoping to slow down the pace of climate change. Yet, behind this progressive image lies an uncomfortable truth. The production and operation of electric cars still depend on resources and systems that cause serious environmental harm. The dream of clean energy, in many ways, has not been as pure as it seems.

The core of every electric car is its battery, which requires large quantities of critical minerals such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, and manganese. Mining these materials demands extensive land clearing, high water use, and chemical processing that can contaminate soil and rivers. In many countries, supply of these minerals has resulted in deforestation, biodiversity loss, and pollution. In Indonesia specifically, nickel mining in Sulawesi and Halmahera has damaged coral reefs and coastal ecosystems, turning once-clear waters into muddy waste streams. Reports from Brookings Institution (2025) and Kompas Lestari (2025) reveal that nickel extraction, which is crucial for EV batteries, has destroyed mangrove areas and polluted fishing zones. Ironically, the “green technology” intended to protect the planet is also contributing to environmental damage.

The environmental cost does not stop at mining. The process of refining and transporting these minerals also requires enormous amounts of energy. Factories producing electric vehicle batteries in Asia and Europe still rely heavily on coal-based electricity. According to OECD (2023) battery production emits between 70–110 kg of CO₂ per kWh capacity, meaning that producing one EV battery can generate more carbon emissions than manufacturing a conventional car engine. Although electric vehicles emit less CO₂ during their use, it can take between 3 to 10 years of driving before their total emissions become lower than traditional cars. If the grid still depends on coal, as is the case in many parts of Indonesia, the concept of “zero emission” becomes misleading.

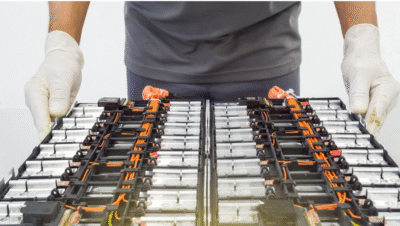

Lithium battery in EVs. stock.adobe.com | Nischaporn

The issue of battery waste is another environmental threat that cannot be ignored. Most electric car batteries have a lifespan of around eight to ten years. When they reach the end of their life cycle, improper disposal can release toxic materials such as lithium, cobalt, and heavy metals into the environment. Currently, only about 5–10% of lithium-ion batteries are recycled globally (Statista, 2025). This figure remains low due to the high cost and complexity of recycling. In Europe, Associated Press (2025) reports that large-scale battery recycling is still unprofitable, while developing countries like Indonesia lack the infrastructure and regulations to manage this waste safely. Without a proper recycling system, the rapid growth of the EV industry risks creating a new wave of hazardous waste.

Beyond the environmental dimension, there is also a profound social aspect. The expansion of mining areas for electric car materials often occurs near indigenous lands and small rural communities. People who once depended on forests and rivers are now facing displacement and water scarcity. The International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA) documents how indigenous groups in Central Halmahera have lost access to clean water and forest resources due to nickel mining. The extraction sites leave behind degraded landscapes and contaminated water sources, while the benefits of this “green revolution” are enjoyed by urban populations and foreign investors. This creates an ethical paradox, as the pursuit of global sustainability has come at the expense of local justice.

This paradox highlights that technology alone cannot guarantee sustainability, which instead requires transparency, ethical responsibility, and awareness of interconnected systems. Clean transportation should not depend on harmful mining, so the future of energy must pair innovation with accountability. Electric vehicles can reduce air pollution and fossil-fuel reliance, but only when supported by responsible mineral sourcing, renewable-based electricity, and effective recycling systems. Reports from the Nickel Institute (2025) note that integrating renewable energy into production, extending EV battery life, and exploring alternative chemistries can greatly lower environmental impacts.

Minerals mining activity. stock.adobe.com | Ugurhan

Even so, electric vehicles still represent a step forward compared to gasoline-powered cars. Data from Generali Indonesia (2025) show that, over their full lifecycle, EVs emit 30–50% less carbon than conventional vehicles as long as the electricity grid continues shifting toward renewables. This means EVs are part of the solution, but not the ultimate one, because they still carry environmental and social costs. Recognizing these limitations allows society to push for improvements such as stricter mining regulations, better battery recycling, circular economy models, alternative chemistries like sodium-ion or solid-state, and battery production powered by renewable energy. The goal is to create green mobility that is genuinely sustainable rather than assuming it is harmless simply because it produces no tailpipe emissions.

It is time for all of us to rethink what we call “green.” We must not only understand how technology works but also question its hidden costs. Collective awareness and action are essential to ensure that innovations truly bring harmony between humans and nature. Protecting Mother Nature requires more than adopting new technologies, it requires a transformation in how we respect the balance of life that sustains us all. By discussing and proposing concrete solutions while critically observing their limitations, we can ensure that steps like the transition to electric vehicles are part of a genuinely sustainable path rather than a superficial fix.

References

Brookings Institution. (2022). Indonesia’s electric vehicle batteries dream has a dirty nickel problem. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/indonesias-electric-vehicle-batteries-dream-has-a-dirty-nickel-problem

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2023). NEW BUT USED: The Electric Vehicle Transition and the Global Second-Hand Car Trade. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2023/12/new-but-used_33bd60ec/28ee4515-en.pdf

Statista. (2025). Battery recycling worldwide – statistics & facts. https://www.statista.com/topics/9962/li-ion-battery-recycling/

Nickel Institute. (2025, July). Critical minerals driving EV performance: a consumer Guide to EV batteries. https://nickelinstitute.org/en/blog/2025/july/critical-minerals-driving-ev-performance-a-consumer-guide-to-ev-batteries-part-1

Kompas Lestari. (2025, June 10). Narasi Hijau Palsu: Dampak Nyata Tambang Nikel di Balik Mobil Listrik. https://lestari.kompas.com/read/2025/06/10/053937886/narasi-hijau-palsu-dampak-nyata-tambang-nikel-di-balik-mobil-listrik

Generali Indonesia. (2025). Mobil Listrik vs Mobil Konvensional, Sudah Tahu Bedanya?. https://www.generali.co.id/id/healthyliving/1/mobil-listrik-vs-mobil-konvensional-sudah-tahu-bedanya